We wrapped up our VSA assignment and left Dili on 1 April. There was no time for a final coffee at Padaria, a snorkel at Back Beach, a spend-up at the tais market, as I’d imagined. Instead, it was a mad rush to finish my Tetun guide to creative writing. Matadalan Hakerek Kreativu evolved into a 140-page book, including four of my students’ stories about women in the Timorese resistance movement, thanks to journalist Nuno Rodriguez who trusted me to teach creative writing in a language I could barely speak. It was the highlight of my time in Timor, a reminder that if you keep the space open, your passion will find you. Here’s more about the guide and the classes.

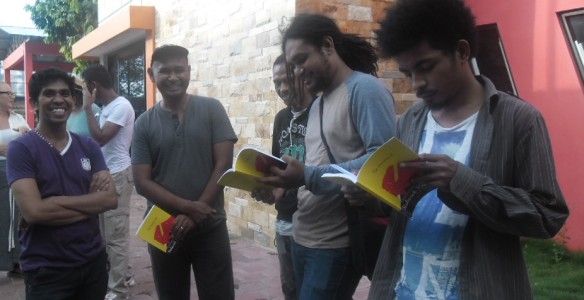

Launching my Tetun guide to creative writing just before we left Timor was a thrill. Nuno, who inspired me to write the guide, is on my left. The banner behind us reads, ‘I write, I live’.

For me, it was worth the last-minute frenzy to see the guide launched at the Xanana Reading Room two days before we left. But it was tough on Pat who had to lay it out in between handing over two years of work at World Vision, and ferry 150 copies home from the printer on his scooter an hour before our farewell party.

Some people we’ve met while we’ve been away will be lifelong friends, others we may never see again. Development workers are a transitory lot, trundling through Timor like an escalator before scattering around the globe.

Pat, draped in a traditional woven tais from his colleagues, cuts his farewell cake at World Vision. His boss, Samaresh, looks on.

The Timorese must be weary of saying good-bye to malae (foreigners, pronounced ma-lie), but they do it with grace. At Pat’s farewell lunch at World Vision, his boss Samaresh and co-workers praised his softly, softly approach. He gets alongside people and makes them believe in themselves. He has transformed the organisation’s communications. They’ve signed up more Kiwi volunteers.

Monik, who recently won a scholarship to the Dili International School, presents me with a farewell tais.

A hundred students from the English evening classes I’ve coordinated put on a farewell party for me. One had written a song, another a poem. There were speeches and food. I got so many tais they had to start hanging them around Pat’s neck.

Leaving these bright young folk was a wrench, aggravated by the nagging question, will we ever return? Family, friends and familiarity pull you home. But what takes you back to a place that’s not your own?

Already, Timor’s fading. I can picture myself walking along the river road past kids in fluoro school uniforms, pigs rooting in rubbish, palm fronds splayed against the sky like tarantulas. But the sounds and smells are elusive and it’s hard to conjure up the stickiness in the face of Wellington’s autumn chill.

I miss the warmth of Timor, both her climate and people. I miss the babble of languages and the thrill of speaking strange sounds that other people understand. I miss the sense of purpose. It takes a long time to make a difference but the need is clear and the locals are remarkably tolerant of our attempts.

I miss the simplicity. VSA found us an apartment and provided an instant community. Our motor scooter cost $2.50 a week to run. We cooked on a two-ring gas burner. There’s nothing to buy. For Pat and me, it was like a second honeymoon, free of the ties that have tugged us this way and that for as long as I can remember.

Oh, and I miss being tall.

On our way home, we stopped in Oz for a couple of weeks to visit friends and re-adjust to credit cards and motorways. It was great to debrief with fellow volunteer and Dili neighbour Julia who has gone on to work in Alice Springs. Sharing resettlement qualms with those who haven’t been there is harder.

People ask, are you pleased to be home? It feels like a test, my ‘yes’ or ‘no’ a judgement on their choices as much as my own. I don’t want to turn it into a competition. There’s so much to love about New Zealand. Sausages cooked over an open fire with the grandkids. Sisters. Crisp salads. Rinsing my toothbrush under the tap. DKNY perfume, not Dili DEET.

But the First World doesn’t have all the answers. It’s taken over a month for our unaccompanied luggage to get from Auckland to Wellington, and nearly three weeks to get internet connected. No one just sits. And I’ve passed more homeless people begging in central Wellington than I ever saw in Asia’s poorest country.

Would we volunteer again? Another two-year stint’s unlikely. Our youngest grandchild was three when we left; he’s just started school. That’s a lot of cuddles to miss out on. But if I’ve learned one thing, it’s that the line between staying and going is not as rigid as I thought. After 30 years in the same house, you can pack up, head off, return, and the sky stays put. More scary, in fact, is how little changes. You’re not even sure if you have.

Pat’s going to build on the experience by working part-time for VSA, connecting returned volunteers. I’m not sure what the future holds for me. Before we set off, my big bro Matt, who’s helped out in Asia for 25 years, said living in a new culture would renew our feeling of awe: both awe-some and awe-ful. He was right. The challenge is to maintain the same sense of wonder here, at home, in the awe-dinary .

This is our last Dili Dally blog. A big thank-you to all our readers for your interest and support. You can still find us at 2Write, our communications business.

If you live in Wellington and want to know more about Timor, please come along to Exploring Timor-Leste, an exhibition of craft, photographs, paintings, music and stories. It’s running at the Thistle Hall at the top of Cuba Street until Sunday 10 May.

Obrigada barak

Pip